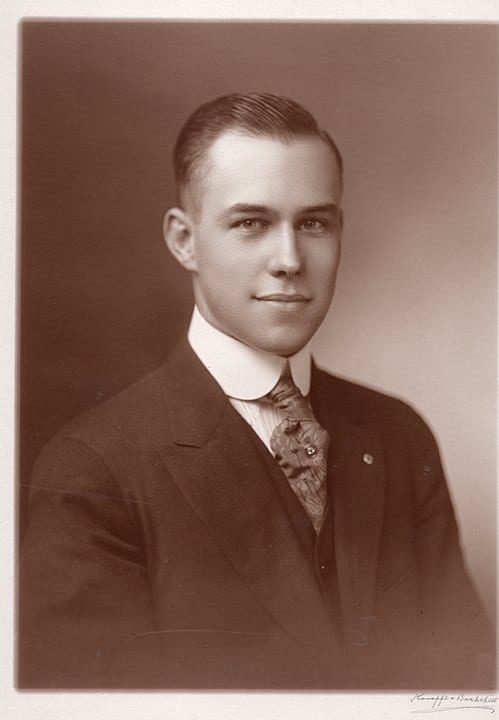

Harry T. Burn. Remember that name. It will come up later.

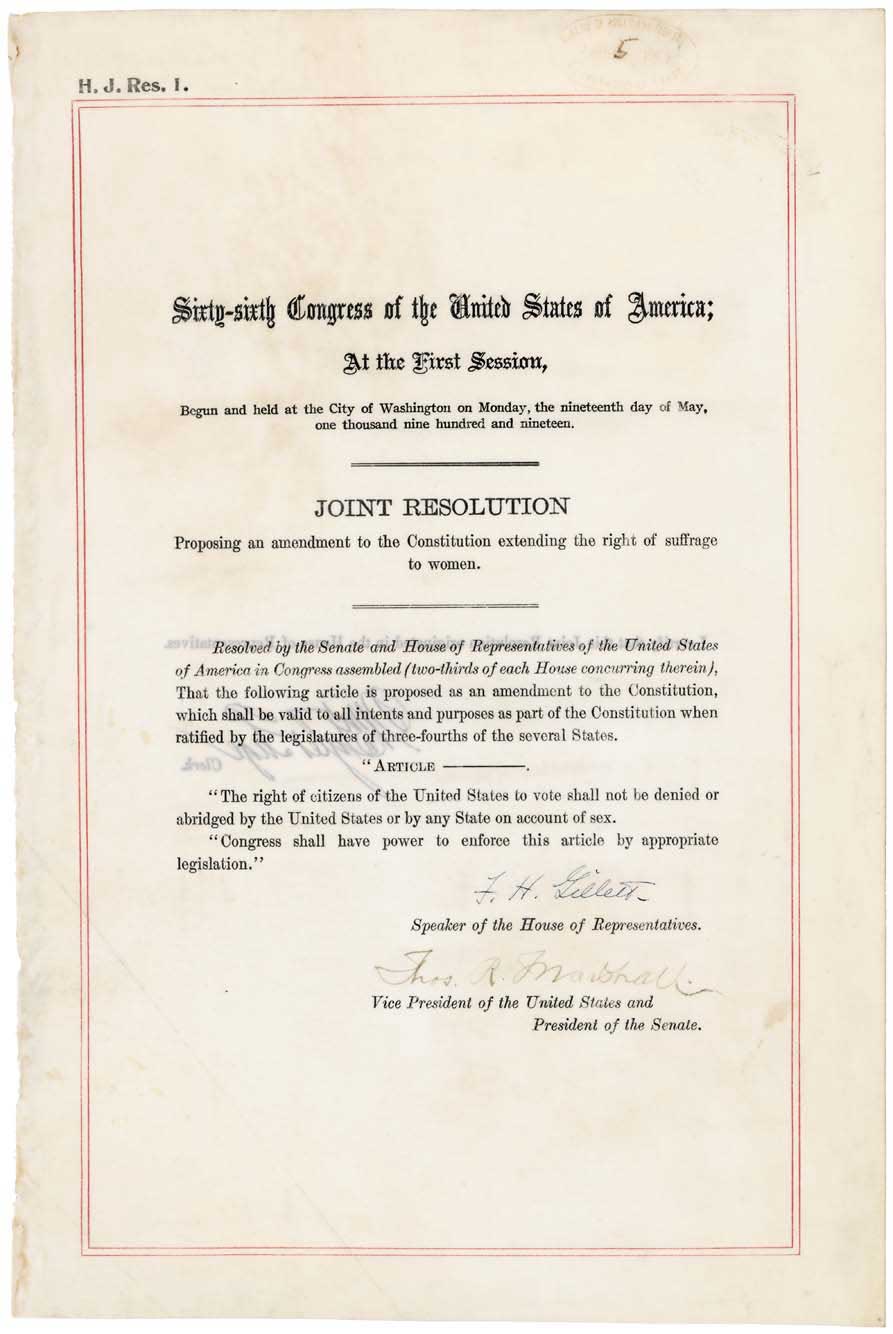

Things were looking good for America’s women suffragists in May 1919, when the 19th Amendment to the Constitution, which would make a woman’s right to vote official in the U.S., came up on the floor of the House of Representatives. The 19th needed a two-thirds majority to pass, and no Hail Mary, last-minute maneuvers were needed—it sailed to approval by a margin of 304-89, a full 42 votes more than the two-thirds needed.

Suffragists and supporters were a bit more nervous when weeks later, in June, the Senate had its chance to vote. But while the vote was much closer, the amendment passed 56-25, just two votes over the two-thirds majority needed.

WomensVote100.shop – Celebrate the 2020 centennial of the 19th Amendment by supporting the work of WomensVote100.org. The shop opens Friday, Nov. 29, 2019.

Even with the blessing of Congress, supporters of the 19th couldn’t celebrate quite yet. The Amendment was sent to the states for ratification where, before it could be officially added to the Constitution, it had to have the support of three-quarters of them.

It took only six days for the first three states to sign on, and three more ratified it shortly after. By March 1920, 35 states had officially supported the 19th—only one state less than what was needed.

The last domino didn’t fall easily, and this is where Mr. Burn’s name comes up in a very big way. The American South was a stronghold of opposition to the 19th and seven southern states, including Virginia, had voted against the Amendment before the Tennessee legislature took up the issue in August 1920. Tennessee was the last state that would be voting that year, making it the last hope for suffragists for at least months.

While some say that Mr. Burn’s role has been somewhat embellished over time, the fact is that the issue had largely come down to the results in Tennessee and lobbyists on both sides were working furiously to influence the vote. The outcome was too close to call, and Nashville was deep in suspense.

Burn, who was only 24, originally voted to postpone the vote until the next legislative session, but a late change of heart by others brought the issue to the floor and forced the vote.

When it came time for Burn to cast his vote, the legislature was locked in a 48-48 tie. He surprised many with his “aye” vote and later told others that he was carrying a letter from his mother in his suit pocket, telling him to be “a good boy” and urging him to support the 19th.

He later explained his vote this way: “I knew that a mother’s advice is always safest for a boy to follow and my mother wanted me to vote for ratification. I appreciated the fact that an opportunity such as seldom comes to a mortal man to free 17 million women from political slavery was mine.”

With his vote, the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution became officially ratified, becoming the law of the land in August 1920 after official documents were signed in Washington, D.C.

WomensVote100.shop – Celebrate the 2020 centennial of the 19th Amendment by supporting the work of WomensVote100.org. The shop opens Friday, Nov. 29, 2019.